By Stuart Dowell

Today marks 80 years since the start of the Warsaw Uprising, the largest single resistance operation of World War Two. After 63 days, and the loss of up to 200,000 lives, the Polish forces finally succumbed to brutal repression by the German occupiers.

The Germans then expelled the hundreds of thousands of civilians remaining in Warsaw before systematically destroying the city. However, groups of survivors decided to remain among the ruins. They became known as Warsaw’s “Robinson Crusoes” and this is their story.

When Władysława Lewandowska gave birth to her daughter on 1 December 1944 it should have been a moment of joy, signalling hope after years of war and occupation.

But Lewandowska was among a small group who had defied German orders to evacuate Warsaw after the uprising’s fall. For those hiding in the ruins on Ogrodowa Street, a crying baby meant imminent discovery – and death.

The group convened immediately after the birth, initially deciding that the danger must be eliminated and that the mother should undertake the grim task. Fortunately, they then devised another plan. The baby was placed in a metal bathtub and smothered with a pillow whenever it cried. Within three days, the infant learned not to cry.

A German soldier setting fire to buildings following the fall of the Warsaw Uprising (photo credit: German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons, under CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Other such groups of hardy souls existed across the city, living among the ruins, known by Poles as “Robinson Crusoes” but derisively called “rubble rats” by the Germans.

They believed they would need to hide for just a few days before the advancing Red Army marched into the city and liberated them. In fact, their epic struggle to survive continued for over three months as the Soviets would only enter Warsaw on 17 January 1945.

Across that period, they endured extreme conditions, from the heat of raging fires to the severe cold of winter, all while battling disease, vermin, depression and grief.

A dramatic decision

The Warsaw Uprising, which began on 1 August 1944, officially ended 63 days later on 3 October 1944. After long negotiations with the Germans, the Home Army – the Polish underground resistance – signed a capitulation agreement with Waffen-SS General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski.

The deal recognised the Home Army as a legitimate combatant, thereby giving its soldiers protection from German reprisals. However, it also called for the exodus of all civilians from Warsaw. The Germans sent the beleaguered population to the Dulag 121 transit camp in nearby Pruszków.

Civilians travelling to the Dulag 121 transit camp in Pruszków (photo credit: German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons, under CC-BY-SA 3.0)

On the spot selections took place. Many were sent to concentration camps, while those able to work were deported to the Reich. The remaining – the sick, the elderly, women and children – were put on trains and dumped in the middle of nowhere in occupied Poland.

“The Germans were very anxious that the entire civilian population should leave the city,” says Katarzyna Utracka, a historian at the Warsaw Uprising Museum. “However, this did not happen, because there was a group of people in Warsaw who made the dramatic decision to stay.”

Estimates put the number of castaways at up to a thousand. Some did not want to leave homes that may have miraculously survived the uprising. They hoped that the Red Army would enter any day and life would return to normal.

Some were Home Army soldiers who had been injured during the uprising and could not escape or did not believe the German assurances that prisoners of war would be treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. The article continues below.

They had seen enough of German crimes – roundups, public executions – and preferred to take fate into their own hands rather than be exiled from the city and suffer humiliation in a camp.

“Most of the group, though, were Jews,” explains Utracka. “They feared that the moment they left with the other civilians they would be caught by the Germans, and this risked death on the spot.”

Most of Warsaw’s Jews – who before the war made up a third of its population – had by 1944 been murdered in the Holocaust. The city’s ghetto was destroyed in 1943 after its own uprising. But some Jews had remaining in the city, surviving in hiding.

Other “Robinson Crusoes” were Red Army soldiers who had escaped from their German captors and had no intention of joining the exodus when their own army was just a few kilometres away on the other side of the Vistula river.

The struggle for survival

Dangers lurked everywhere for the castaways. They had to go to great lengths to keep their presence in the ruins secret, which was particularly difficult as footprints could be easily tracked in the winter snow.

Crossing paths with a German official meant certain death, most likely at the hands of the police units tasked to hunt the survivors down.

To survive, the Robinsons organised themselves into small groups, pooling skills and dividing tasks. They drew up strict rules, which had to be closely observed in order not to endanger others.

One group of four Poles hiding in a tenement house on Marszałkowska Street established the following rules:

“Absolute silence must be maintained, no loud talking, coughing, sneezing, etc., conversations may be held only in whispers; no aimless wandering is allowed; zones have been established which must absolutely be avoided; those not on duty have to prepare food; if one of them were to be seriously wounded or ill, the others are required to shorten his suffering by killing him before he betrays his hiding place by moaning or screaming.”

One extreme example of the strict discipline was the case of Jakub Wiśnia, a Jew hiding in a bunker on Twarda Street. When he became thirsty and started to drink water from a precious supply in a bathtub, he was sentenced to death by his Jewish companions. In the end, they commuted the sentence after having a change of heart.

The ruins of the Saxon Palace in Warsaw (photo credit: Jan Bułhak/Wikimedia Commons, under public domain)

The biggest challenge was getting food and water. The most common food to be found in the ruined tenements was tinned food, leftover bread, dried peas and beans.

Water was sourced from broken water pipes, bathtubs and rainwater. In a few cases, groups managed to dig wells. Lack of water and food was the primary reason to leave a hiding place.

Henryk Kowalewski was hiding with his father, who one night went out to search for food. He came back with just some moulding marmalade and coffee. The next night he went out again but never returned.

“I was left alone. I ate the rest of the potatoes and made soup out of the peelings, adding coffee,” Kowalewski recalled after the war. “ At times I lost consciousness from hunger. One day in January I crawled out onto the street. Warsaw had been free for two days.”

One castaway, Wacław Gluth-Nowowiejski, wrote the best-known book on the Robinsons, Don’t Die Until Tomorrow (Nigdy umieraj do jutra). He was wounded during fighting in the Marymont district and miraculously survived a massacre carried out by the Germans in a resistance hospital.

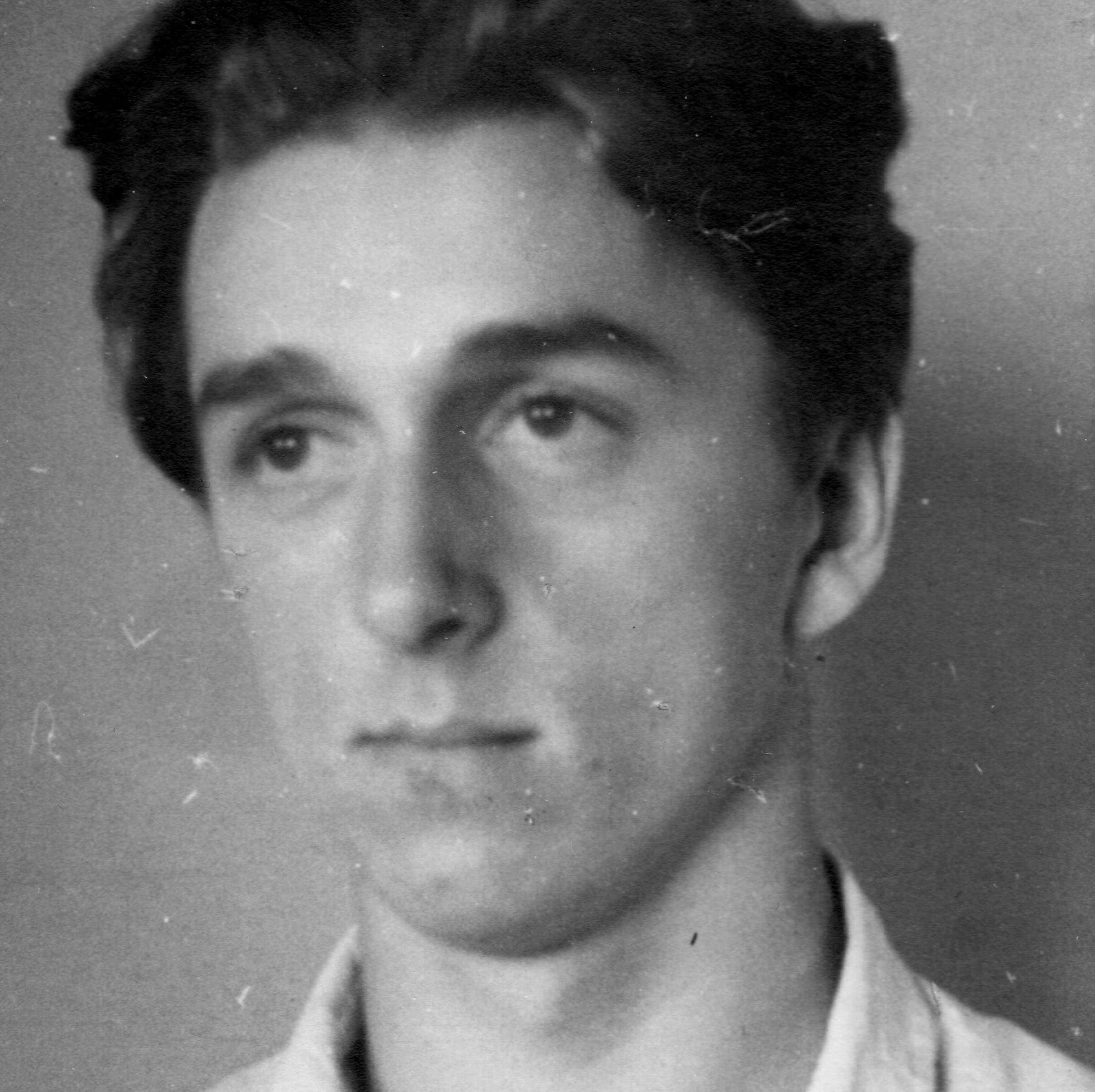

Wacław Gluth-Nowowiejski was 18 years old when he participated in the Warsaw Uprising (photo credit: the Warsaw Rising Museum)

He then hid in the basement of a nearby house, where he remained until mid-November 1944.

“What saved me was the fact that there were two buckets of water and potatoes lying around,” he recalled. “All I can say is that I was not alone…The bugs were all over me. They ate me alive.”

In the book, he recounts the experiences of Czesław Lubaszka, a baker and founder of the Warsaw bakery chain Galeria Wypieków Lubaszka, still popular today.

His three-man group started by looking for a safe and fairly well-equipped hiding place. They chose a cellar at 40 Twarda Street. From the neighbouring houses they brought quilts, blankets and pots.

They also searched for food, of which there was increasingly less following the initial days after the fall of the uprising.

However, Lubaszka managed to find 150 kilograms of flour. He remembered that there was an oven in the cellar of a nearby house and, under the cover of night, baked a dozen or so loaves of bread.

On one of his nightly escapades to the oven, he stumbled across a group of seven starving Jews. The bread that he gave them saved their lives. In return one of the women in the group, Marysia, became his baking assistant.

The most well-known castaway was Władysław Szpilman, who was portrayed by Adrien Brody in Roman Polański’s Oscar-winning film The Pianist.

Before the outbreak of the uprising, he had been in hiding for many months after escaping from the Warsaw Ghetto. His hiding place was in the ruins of a burnt-out house at 223 Niepodległości Avenue, where he was discovered by Wehrmacht officer Wilm Hosenfeld.

After discovering that Szpilman was a pianist, Hosenfeld asked him to play something on a piano inside the building. The officer then brought Szpilman food and a coat, helping him to survive until the Germans retreated from the city.

A bittersweet liberation

Units of the Soviet 47th Army and General Zygmunt Berling’s First Army of the Polish Armed Forces in the East finally crossed the Vistula and entered Warsaw on 17 January.

Out of the initial population of around a thousand, only a few hundred castaways remained. Many died of hunger and thirst, others were discovered and shot by the Germans. Some committed suicide.

The treatment of the survivors by the Soviets varied significantly. Red Army soldiers were often moved by their resilience and provided immediate assistance, such as food, water and medical care.

However, the Soviet authorities and the Polish intelligence services viewed the survivors with suspicion, conducting thorough interrogations to ascertain their identities, wary of potential anti-communist sentiments or collaborators among them.

Additionally, the postwar communist authorities sought to use the plight of the Robinsons for propaganda purposes, highlighting their survival as evidence of German brutality and the failure of the Polish government-in-exile.

Today, little evidence of their struggle remains in Warsaw. A plaque on Marszałkowska Street commemorates four men who hid in the ruins at that address, while earlier this year a square in the city centre was named after the Warsaw Robinsons.